აბაშის ხმა

Каталог статей

| მთავარი » სტატიები » История философия » Авраам Линкольн |

Abraham Lincoln

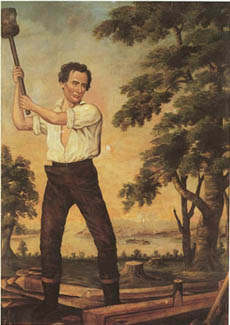

INTRODUCTION Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), 16th president of the united states. Lincoln entered office at a critical period in u. s. history, just before the Civil War, and died from an assassin's bullet at the war's end, but before the greater implications of the conflict could be resolved. He brought to the office personal integrity, intelligence, and humanity, plus the wholesome characteristics of his frontier upbringing. He also had the liabilities of his upbringing--he was self-educated, culturally unsophisticated, and lacking in administrative and diplomatic skills. Sharp-witted, he was not especially sharp-tongued, but was noted for his warm good humor. Although relatively unknown and inexperienced politically when elected president, he proved to be a consummate politician. He was above all firm in his convictions and dedicated to the preservation of the Union. Lincoln was perhaps the most esteemed and maligned of the American presidents. Generally admired and loved by the public, he was attacked on a partisan basis as the man responsible for and in the middle of every major issue facing the nation during his administration. Although his reputation has fluctuated with changing times, he was clearly a great man and a great president. He firmly and fairly guided the nation through its most perilous period and made a lasting impact in shaping the office of chief executive.Once regarded as the "Great Emancipator" for his forward strides in freeing the slaves, he was criticized a century later, when the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, for his caution in moving toward equal rights. If he is judged in the historical context, however, it can be seen that he was far in advance of most liberal opinion. His claim to greatness endures. Early Life and Ancestry The future president was born in the most modest of circumstances in a log cabin near Hodgenville, Ky., on Feb. 12, 1809. His entire childhood and young manhood were spent on the brink of poverty as his pioneering family made repeated fresh starts in the West. Opportunities for education, cultural activities, and even socializing were meager. Lincoln's paternal ancestry has been traced, in an unbroken line, to Samuel Lincoln, a weaver's apprentice from Hingham, England, who settled in Hingham, Mass., in 1637. From him the line of descent came down through Mordecai Lincoln of Hingham and of Scituate, Mass.; Mordecai of Berks county, Pa.; John of Berks county and of Rockingham county, Va.; and Abraham, the grandfather of the president, who moved from Virginia to Kentucky about 1782, settled near Hughes Station, east of Louisville, and was killed in an Indian ambush in 1786. Abraham's youngest son, Thomas, who became the father of the president, was born in Rockingham county, Va., on Jan. 6, 1778. After the death of his father, he roamed about, settling eventually in Hardin county, Ky., where he worked at carpentry, farming, and odd jobs. He was not the shiftless ne'er-do-well sometimes depicted, but an honest, conscientious man of modest means, well regarded by his neighbors. He had practically no education, however, and could barely scrawl his name. Nancy Hanks, whom Thomas Lincoln married on June 12, 1806, and who became the mother of the president, remains a shadowy figure. Her birth date is uncertain, and descriptions of her are contradictory. Scholars despair of penetrating the tangled Hanks genealogy, and the legitimacy of Nancy's birth is a subject of argument. Lincoln, himself, apparently believed that his mother was born out of wedlock. In either case, Nancy came of lowly people. Reared by her aunt, Betsy Hanks, who married Thomas Sparrow, she was utterly uneducated. Young Manhood During the 14 years the Lincolns lived in Indiana, the region became more thickly settled, mostly by people from the South. But conditions remained primitive, and farming was backbreaking work. Superstitions were prevalent; social functions consisted of such utilitarian amusements as corn shuckings, house raisings, and hog killings; and religion was dogmatic and emotional. Abe, growing tall and strong, won a reputation as the best local athlete and a rollicking storyteller. But his father kept him busy at hard labor, hiring him out to neighbors when work at home slackened. Abe's meager education had aroused his desire to learn, and he traveled over the countryside to borrow books. Among those he read were Robinson Crusoe, Pilgrim's Progress, Aesop's Fables, William Grimshaw's History of the United States, and Mason Weems' Life of Washington. The Bible was probably the only book his family owned, and his abundant use of scriptural quotations in his later writings shows how earnestly he must have studied it. Young Lincoln worked for a while as a ferryman on the Ohio River, and at 19 helped take a flatboat cargo to New Orleans. There he encountered a manner of living wholly unknown to him. Soon after he returned, his father decided to move to Illinois, where a relative, John Hanks, had preceded him. On March 1, 1830, the family set out with all their possessions loaded on three wagons. Their new home was located on the north bank of the Sangamon River, west of Decatur. When a cabin had been built and a crop had been planted and fenced, young Lincoln hired out to split fence rails for neighbors. In the autumn all the Lincoln family came down with fever and ague. That winter the pioneers experienced the deepest snow they had ever known, accompanied by subzero temperatures. In the spring the family backtracked eastward to Coles county, Ill. But this time Abraham did not accompany them, for during the winter he, his stepbrother John D. Johnston, and his cousin John Hanks had agreed to take another cargo to New Orleans for a trader, Denton Offutt. A new life was opening for young Lincoln. Henceforth he could make his own way.Supposedly it was on this second trip to New Orleans that young Lincoln, watching a slave auction, declared: "If I ever get a chance to hit that thing, I'll hit it hard." But the story is almost certainly untrue. Lincoln at this period of his life could scarcely have believed himself to be a man of destiny, and John Hanks, who originated the story, was not with Lincoln, having left his fellow crewmen at St. Louis. Near the outset of this voyage, at the little village of New Salem on the Sangamon River, Lincoln had impressed Offutt by his ingenuity in moving the flatboat over a milldam. Offutt, impressed likewise by the prospects of the village, arranged to open a store and rent the mill. On Lincoln's return from New Orleans, Offutt engaged him as clerk and handyman. By late July 1831, when Lincoln came back, New Salem was enjoying what proved to be a short-lived boom based on a local conviction that the Sangamon River would be made navigable for steamboats. For a time the village served as a trading center for the surrounding area and numbered among its enterprises three stores, a tavern, a carding machine for wool, a saloon, and a ferry. Among its residents were two physicians, a blacksmith, a cooper, a shoemaker, and other craftsmen common to a pioneer settlement. The people were mostly from the South, though a number of Yankees had also drifted in. Community pastimes were similar to those Lincoln had previously known, and life in general differed only in being somewhat more advanced. Lincoln gained the admiration of the rougher element of the community, who were known as the Clary's Grove boys, when he threw their champion in a wrestling match. But his kindness, honesty, and efforts at self-betterment so impressed the more reputable people of the community that they, too, soon came to respect him. He became a member of the debating society, studied grammar with the aid of a local schoolmaster, and acquired a lasting fondness for the writings of Shakespeare and Robert Burns from the village philosopher and fisherman. Offutt paid little attention to business, and his store was about to fail, when an Indian disturbance, known as the Black Hawk War, broke out in April 1832, in Illinois. Lincoln enlisted and was elected captain of his volunteer company. When his term expired, he reenlisted, serving about 80 days in all. He experienced some hardships, but no fighting. Politics and Law Returning to New Salem, Lincoln sought election to the state legislature. He won almost all the votes in his own community, but lost the election because he was not known throughout the county. In partnership with William F. Berry, he bought a store on credit, but it soon failed, leaving him deeply in debt. He then got a job as deputy surveyor, was appointed postmaster, and pieced out his income with odd jobs. The story of his romance with Ann Rutledge is rejected as a legend by most authorities, but he did have a short-lived love affair with Mary Owens. His friend Stuart had encouraged him to study law, and he obtained a license on Sept. 9, 1836. By this time New Salem was in decline and would soon be a ghost town. It has since been restored as a state park. On April 15, 1837, Lincoln moved to Springfield to become Stuart's partner. His conscientious efforts to pay off his debts had earned him the nickname "Honest Abe," but he was so poor that he arrived in Springfield on a borrowed horse with all his personal property in his saddlebags. With the courts in Springfield in session only a few weeks during the year, lawyers were obliged to travel the circuit in order to make a living. Every year, in spring and autumn, Lincoln followed the judge from county to county over the 12,000 square miles (31,000 sq km) of the Eighth Circuit. In 1841 he and Stuart disolved their firm, and Lincoln formed a new partnership with Stephen T. Logan, who taught him the value of careful preparation and clear, succinct reasoning as opposed to mere cleverness and oratory. This partnership was in turn dissolved in 1844, when Lincoln took young William H. Herndon, later to be his biographer, as a partner. Marriage Meanwhile, on Nov. 4, 1842, after a somewhat tumultuous courtship, Lincoln had married Mary Todd. Brought up in Lexington, Ky., she was a high-spirited, quick-tempered girl of excellent education and cultural background. Notwithstanding her vanity, ambition, and unstable temperament and Lincoln's careless ways and alternating moods of hilarity and dejection, the marriage turned out to be generally happy. Of their four children, only Robert Todd Lincoln, born on Aug. 1, 1843, lived to maturity. Edward Baker, who was born on March 10, 1846, died on Feb. 1, 1850; William Wallace, born Dec. 21, 1850, died on Feb. 20, 1862; and Thomas ("Tad"), born April 4, 1853, died on July 15, 1871. Though Mrs. Lincoln was by no means such a shrew as has been asserted, she was difficult to live with. Lincoln responded to her impulsive and imprudent behavior with tireless patience, forbearance, and forgiveness. Borne down by grief and illness after her husband's death, Mrs. Lincoln became so unbalanced at one time that her son Robert had her committed to an institution. Congressman Having attained a position of leadership in state politics and worked strenuously for the Whig ticket in the presidential election of 1840, Lincoln aspired to go to CONGRESS. But two other prominent young Whigs of his district, Edward D. Baker of Springfield and John J. Hardin of Jacksonville, also coveted this distinction. So Lincoln stepped aside temporarily, first for Hardin, then for Baker, under a sort of understanding that they would "take a turn about." When Lincoln's turn came in 1846, however, Hardin wished to serve again, and Lincoln was obliged to maneuver skillfully to obtain the nomination. His district was so predominantly Whig that this amounted to election, and he won handily over his Democratic opponent. Lincoln worked conscientiously as a freshman congressman, but was unable to gain distinction. Both from conviction and party expediency, he went along with the Whig leaders in blaming the Polk administration for bringing on war with Mexico, though he always voted for appropriations to sustain it. His opposition to the war was unpopular in his district, however. When the annexations of territory from Mexico brought up the question of the status of slavery in the new lands, Lincoln voted for the Wilmot Proviso and other measures designed to confine the institution to the states where it already existed. Disillusionment with Politics In the campaign of 1848, Lincoln labored strenuously for the nomination and election of Gen. Zachary TAYLOR. He served on the Whig National Committee, attended the national convention at Philadelphia, and made campaign speeches. With the Whig national ticket victorious, he hoped to share with Baker the control of federal patronage in his home state. The juiciest plum that had been promised to Illinois was the position of commissioner of the General Land Office in Washington. After trying vainly to reconcile two rival candidates for this office, Lincoln tried to obtain it for himself. But he had little influence with the new administration. The most that it would offer him was the governorship or secretaryship of the Oregon Territory. Neither job appealed to him, and he returned to Springfield thoroughly disheartened. Never one to repine, however, Lincoln now devoted himself to becoming a better lawyer and a more enlightened man. Pitching into his law books with greater zest, he also resumed his study of Shakespeare and mastered the first six books of Euclid as a mental discipline. At the same time, he renewed acquaintances and won new friends around the circuit. Law practice was changing as the country developed, especially with the advent of railroads and the growth of corporations. Lincoln, conscientiously keeping pace, became one of the state's outstanding lawyers, with a steadily increasing practice, not only on the circuit but also in the state supreme court and the federal courts. Regular travel to Chicago to attend court sessions became part of his routine when Illinois was divided into two federal districts. Outwardly, however, Lincoln remained unchanged in his simple, somewhat rustic ways. Six feet four inches (1.9 meters) tall, weighing about 180 pounds (82 kg), ungainly, slightly stooped, with a seamed and rugged countenance and unruly hair, he wore a shabby old top hat, an ill-fitting frock coat and pantaloons, and unblacked boots. His genial manner and fund of stories won him a host of friends. Yet, notwithstanding his friendly ways, he had a certain natural dignity that discouraged familiarity and commanded respect. Return to Politics Lincoln took only a perfunctory part in the presidential campaign of 1852, and was rapidly losing interest in politics. Two years later, however, an event occurred that roused him, he declared, as never before. The status of slavery in the national territories, which had been virtually settled by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850, now came to the fore. In 1854, Stephen A. Douglas, whom Lincoln had known as a young lawyer and legislator and who was now a Democratic leader in the U. S. SENATE, brought about the repeal of a crucial section of the Missouri Compromise that had prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase north of the line of 36degrees 30&;. Douglas substituted for it a provision that the people in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska could admit or exclude slavery as they chose. The congressional campaign of 1854 found Lincoln back onthe stump in behalf of the antislavery cause, speaking with a new authority gained from self-imposed intellectual discipline. Henceforth, he was a different Lincoln--ambitious, as before, but purged of partisan pettiness and moved instead by moral earnestness. The Kansas-Nebraska Act so disrupted old party lines that when the Illinois legislature met to elect a U.S. senator to succeed Douglas' colleague, James Shields, it was evident that the Anti-Nebraska group drawn from both parties had the votes to win, if the antislavery Whigs and antislavery Democrats could united on a candidate. However, the Whigs backed Lincoln, and the Democrats supported Lyman Trumbull. though Lincoln commanded far more strength than Trumbull, the latter's supporters were resolved never to desert him for a Whig. As their stubbornness threatened to result in the election of a proslavery Democrat, Lincoln instructed his own backers to vote for Trumbull, thus assuring the latter's election. | |

| ნანახია: 4710 | |

| სულ კომენტარები: 0 | |

მოგესალმები Гость

შესვლის ფორმა |

|---|

ძებნა |

|---|

მინი-ჩეთი |

|---|

საიტის მეგობრები |

|---|

სტატისტიკა |

|---|